How We Choose Projects

For more than 20 years, HRDAG has been carving out a niche in the international human rights movement. We know what we’re good at and what we’re not qualified to do. We know what quantitative questions we think are important for the community, and we know what we like to do. These preferences guide us as we consider whether to take on a project. We’re scientists, so our priorities will come as no surprise. We like to stick to science (not ideology), avoid advocacy, answer quantifiable questions, and increase our scientific understanding.

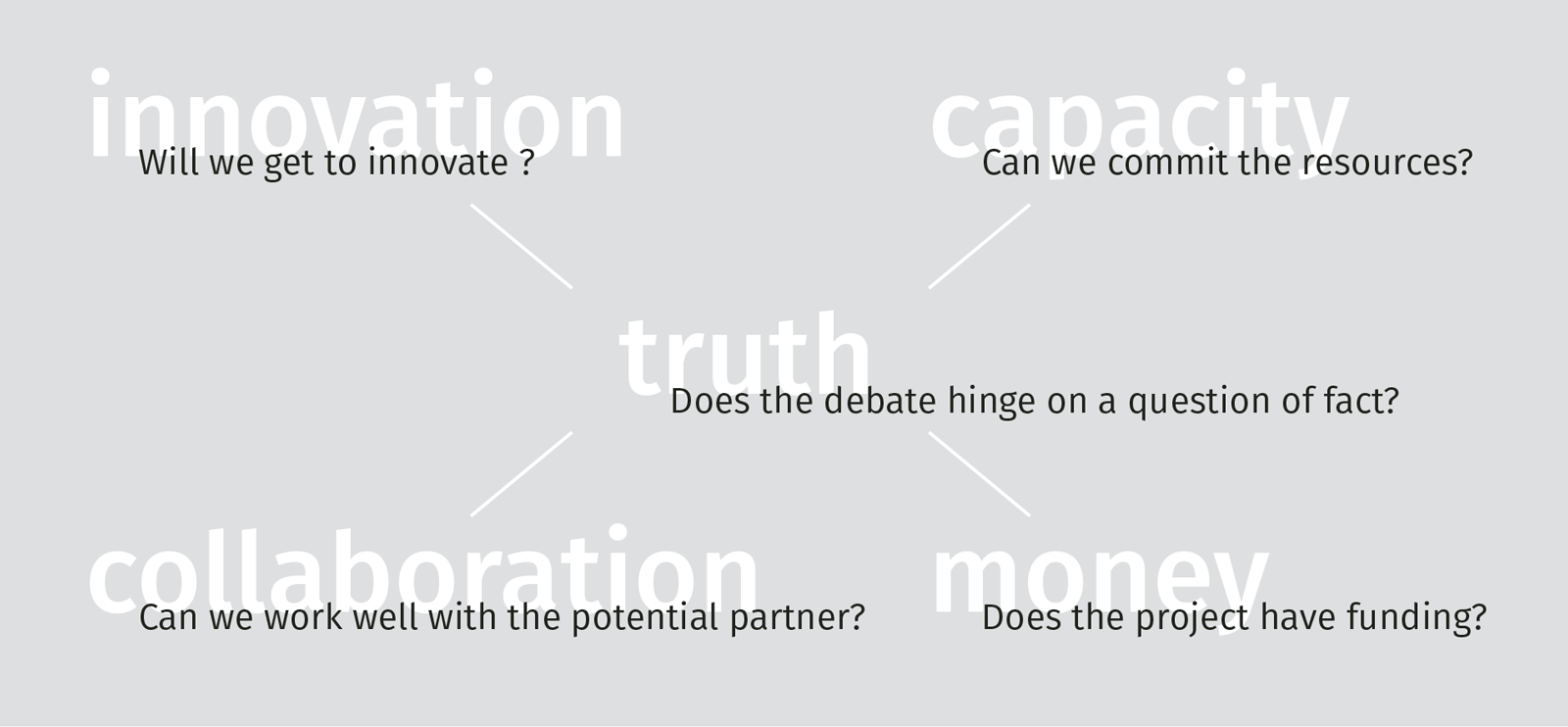

While we have no hard-and-fast rules about what projects to take on, we organize our deliberation using five criteria. The criteria serve as a framework for discussion; in most cases we’ve found that during these discussions, it becomes apparent whether a new project or partner is a good fit.

There are always more projects than we can do. Since 2006, we have used these guidelines to determine whether we should take on a proposed new effort. None of the points is indispensable, and it is not a vote. These questions guide discussion more than determine its outcome. In practice, we find that projects tend to do well, or poorly, on most criteria, and therefore once discussed, the decisions are obvious.

- 1) Does the debate hinge on a question of fact?

We first ask if the truth matters. More specifically, if we were able to establish some key point of statistical fact, would our partners’ advocacy become stronger, would a prosecutor’s case be strengthened, or would a debate about history change? This may be the most important criterion for us—if the question is one of quantity or patterns, then we’re interested. If, however, the question is one of ideology, we’re out; qualitative, rhetorical arguments are not are strength; our strength is quantitative analysis.

Recently, Patrick Ball was invited by Guatemala’s attorney general, Claudia Paz y Paz, to testify for the prosecution in the trial of General Ríos Montt. The prosecution needed to settle questions of fact. How many indigenous Ixil Maya were killed by government forces? Was there a pattern to the killings? HRDAG analysis supported her charge that General Ríos Montt was responsible for a pattern of ethnic cleansing in Guatemala. In May, when General Ríos Montt was convicted of genocide and sentenced to 80 years in prison, the presiding Judge Yassmín Barrios Aguilar cited Patrick’s testimony in her verdict. This is an excerpt from Doctora Barrios’s verdict: “It explains thoroughly the equation, analysis, and the procedure used to obtain the indicated result.”

We can look at another example from 2006, when HRDAG examined the data analysis performed for the Commission on Reception, Truth and Reconciliation (CAVR) of Timor-Leste. In that case, as in the Guatemalan trial, there was a question of scale and pattern. HRDAG’s analysis clarified discrepancies among the number of deaths that resulted from killings and the number of deaths that resulted from excess mortality (hunger and illness). As part of this work, the team created a human rights violations database, developed a retrospective mortality survey, and visited public cemeteries in Timor-Leste to create a graveyard census database.

There are international human rights conundrums that do not involve questions of statistics—and these are the questions that we don’t address. The debates about these conflicts do not involve data, so there’s nothing we could add. In the Palestine-Israel conflict, for example, the statistics are not disputed, so there is nothing that HRDAG can contribute to clarify the argument. In the case of Northern Ireland, the situation is similar: the debate is political, not mathematical.

- 2) Will we get to innovate?

One of our next considerations is what science and technology would be needed in a prospective project. We are most interested in projects that require small innovations on our existing skill and software base: we neither want to remain static nor to take on projects that involve too much risk. When a project hits our sweet spot, requiring us to learn and innovate, with a reasonable expectation of success, we want to do it.

- 3) Can we commit?

For better or for worse, projects don’t end when the analysis is done. Team members can be asked to testify in trials, or called upon to rebut criticism, or asked to present their findings and methods at conferences long after the initial data collection and analysis was conducted. So one of our criteria is whether there will be at least one member of the HRDAG extended team—a staff person, a consultant, or an emeritus—who is willing to make sure the project gets done and then be available for the postpartum work. We’re grateful to Dr Daniel Manrique-Vallier for his stewardship of the work we did in Perú, and likewise to Dr Romesh Silva and Dr Jeff Klingner for their long-term commitment to the work in Chad and the case against former dictator Hissène Habré.

- 4) Can we work well with the potential partner?

We need to work with a partner who either knows exactly what her question of fact is, as was the case with Ms. Paz y Paz in Guatemala, or is willing to work with us in an iterative process to determine what the question of fact is. Our work with the Historic Archive of the National Police (AHPN) of Guatemala is a classic example of that iterative process. For many years, HRDAG team members worked with the AHPN to determine what kind of information was contained in the trove of police documents discovered at the forgotten Archive. Over time, we were able to develop questions that could be answered by the data contained in the documents, and a conceptual question—what happened to Edgar Fernando García?—was re-framed as a quantitative one that could be answered with data.

Partners need to be able to provide data, or to help us find it; to explain the historical and political circumstances to us; and to be willing and able to explain the results to their community or use the results in their advocacy. They do not have to be statistical experts! We’ve had many great partners over the years. Great partners can be as big and well resourced as the International Criminal Tribunal for former Yugoslavia (ICTY), or as small and ad hoc as the International Center for Human Rights Research (CIIDH) in Guatemala.

- 5) Does the project have funding?

Finally, we ask if the project has funding. Sometimes we raise funds together with our partners. If a project interests us, but the partner doesn’t have robust funding, we may in some cases draw on core support from our donors to make an under-funded project feasible for us. We can’t think of a better example of why core support from our donors is so valuable to us.

[Creative Commons BY-NC-SA, excluding photo]