Reflections: A Simple Plan

Amelia Hoover Green, Daniel Guzmán, Patrick Ball, Diego Galindo / Bogotá, 2007 / Comisión Colombiana de Juristas

I got an email from my superheroic PhD adviser in June 2006: Would I be interested in relocating to Palo Alto for six months in order to work with Patrick Ball at the Human Rights Data Analysis Group? (She’d gotten a grant and would cover my stipend.) Since I’d spent the last several months in New Haven wrestling ineffectually with giant, brain-melting methodological problems, I said yes immediately.

The plan with my adviser was simple: I’d digitize the ancient, multiply-photocopied pages of data from the United Nations Truth Commission for El Salvador, combine them with two other datasets, match across all the records, and produce reliable estimates of several types of casualties in the Salvadoran civil war. (Spoiler alert: this is not actually a simple plan.)

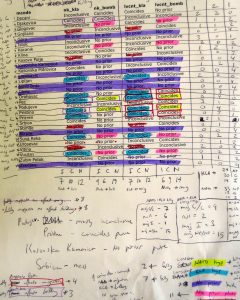

Evaluations by Amelia Hoover Green and Meghan Lynch on alternate hypotheses for Milutinovic et al. / March 2007

I arrived in Palo Alto in early January 2007, started work at HRDAG (then in incubation at the Benetech Initiative) a few days later, and never really left. My colleague Meghan Lynch and I, wearing our Social Scientist hats, helped evaluate alternative hypotheses to explain reported patterns of killings in Colombia and the covariation of homicides and forced displacement in Kosovo. On our off-hours, such as they were, Patrick and I discussed El Salvador, where he had helped build a first-generation human rights database just after the war, and where I was — at least theoretically — headed for dissertation field work. Of course, all the substantive work was built on a mountain of technical skill, most of which was new to me. I learned bash, R, LaTeX, the principles of version control, a smidge of Python, and some machine-learning basics. I scanned hundreds of pages of Salvadoran violence data, wrangling ABBYY Finereader’s finicky spreadsheet OCR function with the assistance of Benetech’s Bookshare team.

Since then, with HRDAG colleagues, I’ve assisted with work for the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia, the International Criminal Court, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission for Liberia, and an Obama-era prosecution of Salvadoran war criminals hiding (in plain sight, since the Reagan administration) in the US. I even finished my dissertation, although my field work ambitions didn’t precisely pan out, and got an academic job.

In at least one way, though, in 2017 I’m right back where I started: estimating patterns of violence against civilians in El Salvador. The push to uncover the true pattern of violence in this war has gained new urgency since last summer, when El Salvador’s highest court struck down its post-war amnesty law, which allowed war criminals big and small to evade accountability. Slowly, cases abandoned in the aftermath of the conflict are being reopened. But, while exhumations proceed at known massacre sites such as El Mozote, broader patterns of violence in El Salvador remain unclear. Indeed, while news stories and some academic accounts confidently state that “70,000” or “75,000” were killed, only about 20,000 unique victims were ever identified by any source. What happened to the rest?

HRDAG has used multiple systems estimation (MSE) to estimate death tolls in Guatemala, Perú, Kosovo, Sri Lanka, Colombia and several other conflicts. The problem in the Salvadoran case is very sparse data, with very uneven coverage. For example, we know a lot about what happened in the capital city, San Salvador — partly because it was a center of violence, and partly because urban areas were more accessible to journalists and rights defenders during the conflict. Although we know about many large massacres, we know vanishingly little, in comparison, about day-to-day violence in rural areas, where civilians were often (but how often?) killed en masse by bombs dropped from American-supplied attack helicopters. Putting at least part of this previously untold story on rigorous statistical footing will help academics like me understand more about patterns (and therefore also about causes) of violence against civilians. More importantly, it may provide incremental help to advocates in a decades-long fight against impunity.

What have I learned in a decade? I’ve tried, sometimes successfully, to assimilate the constant churn of new technical and statistical tools for human rights work. More importantly, I’ve learned that there is no purely technical, judgment-free solution to casualty counting, only better and worse ways of being transparent about our judgments. Take MSE: in a decade we’ve moved from choosing a single best model based on a couple of statistical criteria — omitting uncertainty about the model itself from final estimates — to a framework that averages over all possible models, explicitly incorporating judgment calls and uncertainties into the final estimates. I’ve moved from a quixotic conviction that only good data are useful to a less self-defeating crusade: for transparency, against false precision. We can’t assume good data, but we can’t wait for it, either.